In 1985 out of the State University of Montana an economic professor had the right idea.

An idea before its time. It is now 2010 twenty-five years latter, and the time is now. The time is now to start the path diligently and with true applied force to end all taxation one venue at a time?

The precedents are well in place as of 2010 for theft of the population's wealth and productivity value. Done systematically with our government being run by attorneys exercising corporate precision in the perpetuation of easy money on a massive scale for the benefit of the inside track.

They entertain the population with the seriousness of the current circumstances and planed distraction as they chuckle behind closed doors as and while the massive stacks of cash changes hands under their control, at their discretion; and primarily done so perpetuating their own empire building large and small both domestic and internationally. .

Mr. Edwards writings are not for the entertainment of the Simpson's mentality. It is geared for the intelligent and educated mind having the ability for comprehensive cognitive thinking. His writing is in depth with references given. Please share with your friends that have business backgrounds and also with you local government officials and educators.

Sent FYI from,

Walter Burien - CAFR1

To automatically subscribe to CAFR1 NATIONAL posts - http://CAFR1.com/phplist/?p=subscribe

Mr. Edwards is an associate professor of economics at Montana State University-Northern.

FINANCING GOVERNMENT WITHOUT TAXATION

by James Rolph Edwards

"Winter of 1985"

Reflection upon the malevolent inclinations of some individuals and the necessity for a single set of laws in a given area has caused even most libertarians to conclude that government is a necessary institution, without which civilization would be impossible. But it is also a dangerous and malignant institution. As such its legitimate functions must be rigorously defined, then specified in a constitution which limits government to those functions, and provides institutional checks on the concentration and growth of government power.

Proceeding from rationalist-individualist philosophy, libertarians have developed the clearest and most consistent criteria ever devised for distinguishing the legitimate from the illegitimate functions of government. The argument proceeds as follows: First, no one has the right to initiate the use of force against anyone else, though each individual has the right to its defensive and retaliatory uses. Second, the state gets all of its authority from its citizens, and they cannot grant to government rights they do not have. Hence government is simply the institutional repository of the defensive and retaliatory uses of force. It protects people from each other and from outsiders so that they must interact on a voluntary, contractual basis. All redistributive programs, morality legislation, price controls and so on are ruled out a priori.1

Despite being far superior to any comparable theory of governmental function, even this scheme displays apparent flaws. For one, it seems to make no provision for the allocation of property rights, which is at least in part a government function, necessary in order to reduce externalities so that the market can allocate resources efficiently. This problem is more apparent than real, however. The notions of the illegitimacy of force and fraud, and of the legitimacy of contract (and of governmental enforcement of contract) all rest upon the presupposed existence and legitimacy of property. People who have the right to own and transfer property, and even acquire it through the appropriation of previously unowned resources, have the right to vest government with the authority to register and protect such property, as well as to codify the rules for its legitimate acquisition. These powers do not involve the initiation of coercion.

A more serious objection derives from the supposed necessity of taxation to support even the minimal state. If true, the contradiction is profound. How can the state, which gains its legitimate authority from the rights of individuals, which do not include the right to initiate coercion, finance itself through taxation, which is inherently coercive? More than one critic of libertarian thought has dismissed it on this basis. Libertarians themselves have been split on the issue, some (the anarcapitalists) choosing to believe that the state can be abolished, and others (the minarchists) choosing to suffer the contradiction for the sake of the minimal state.2 Oddly enough, even the number of libertarians who have seriously attempted to conceive of methods of financing the state without taxation is small.

It may be less difficult to devise such a scheme than many people assume. Consider the current situation in which the U.S. government is taxing and spending at very high levels. Now suppose political conditions allow a reduction in the budget and elimination of extraneous programs such that government was spending money only on its legitimate functions. Suppose, moreover, that it continued taxing at current levels and deposited the surplus. The government could continue depositing its surplus revenue each year until the interest on its deposits became large enough to entirely finance its annual expenditures, at which point all taxation could be eliminated. Indeed, the power to tax or borrow money could be eliminated.

Put another way, what the government would be doing in running a surplus is operating with a positive cash balance, rather than a negative cash balance (debt). It is often argued in opposition to proposals for balanced budgets, that the government must be allowed to run deficits and borrow money in order to be "able" to match fluctuating revenue and expenditure flows. A sillier argument is difficult to imagine. Fluctuating revenue and expenditure flows can be matched just as easily by drawing a positive cash balance up or down when required, as by adjusting debt.3

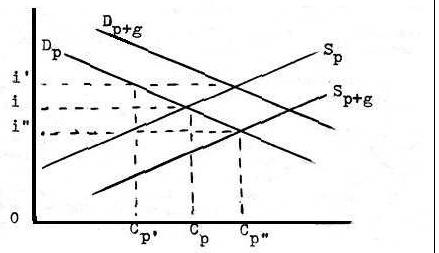

The benefits of financing the federal government from interest on its cash balance would be enormous and would begin with the first surplus. When the government runs a negative cash balance, borrowing money to finance a deficit, it raises interest rates and "crowds out" private borrowers. Consider a graph in which D p and Sp represent the private demand for and supply of credit, and i is the resulting market rate of interest. Cp is the dollar value (in billions) of credit purchased by the public, in order to finance the purchase of capital goods and durable consumer goods, including housing.

Now assume that the government enters the credit market as a borrower in order to finance a deficit, raising demand to Dp+g the sum of private and governmental demand. The interest rate rises to i', reducing the quantity of credit demanded by private parties to Cp'. The difference between Cp and Cp' is private housing, other durable goods and capital investment lost due to governmental borrowing. This has had detrimental long term effects in reducing U.S. growth rates and employment.4

If instead of running a deficit the government ran a surplus, the supply curve in the credit market would shift from S to S p+g'', lowering the interest rate to i'' and increasing private credit purchased to C p''. The housing and (non-housing) durable goods markets would expand immediately, and the additional capital investment would raise the growth rate of American production over time. Unemployment would fall and jobs would be created for those who lost welfare payments with the elimination of such programs.

The political economy of inflation would also be altered under such a system. Strong incentives currently exist for the federal government to finance at least part of its negative cash balance by selling bonds to the Federal Reserve, which increases the rate of growth in the money stock and adds to the rate of inflation. First, this allows partial escape from the crowding-out problem. Second, since the real rate of interest is the nominal rate minus the rate of inflation, raising the latter term allows the government to covertly repudiate much of the national debt (though this works only until creditors' expectations of future inflation rates adjust and the nominal rate is raised enough to restore the real rate, as finally happened in 1981). Third, inflation raises revenue through bracket creep. 6

Forcing government to live on the revenue from its deposits would eliminate all of these incentives for monetary expansion. Also, under the political conditions supposed, the present temptation for government to use inflation in an attempt to reduce unemployment caused by labor legislation, minimum wage laws, and social programs, would no longer exist. In fact, it might be necessary to remove from government the power to control the money stock to prevent it from deflating in an attempt to raise the real value of its interest revenue. Of course much of the benefit of this system would ultimately come from the elimination of taxes itself. Taxes alter relative prices, and hence disturb the efficient allocation of resources.7 The effect of the present progressive tax structure in motivating significant substitution of leisure for labor and current consumption for investment at the margin is particularly pernicious. All such effects would disappear with the elimination of taxes, resulting in greater economic growth and more efficient allocation of resources. Of course many of these benefits could and should be obtained before the complete elimination of taxation by appropriate reform, say by the substitution of a flat-rate income tax or a value added tax for the present system.

II

There are, of course, certain potential objections to the scheme proposed here which come to mind. It might even be claimed to violate the libertarian theory from which it proceeds. Anarcapitalists in particular will deny that coercive taxation is justified even for a limited period. Even minarchists may object to taxation rates exceeding those required for the finance of legitimate governmental functions over such a period.8 Three responses are in order.

First, it is precisely from recognition of the objectionable nature of taxation that the proposal made here for its elimination flows. Until and unless some other feasible method of financing government without taxation is developed, the real alternative is not the absence of taxation, but perpetual taxation. Surely that is not preferable to taxation for a period that is specifically designed to be self-terminating.

Second, the degree of coercion involved in taxation is not related to the rate of taxation, but is related directly to its coverage and inversely to its support. Clearly the majority of the voting population currently support taxation.9 It is not they who are being coerced, but a dissenting minority which includes some subset of libertarians. Might not even this minority be severely reduced if its members know that current tax revenues were being used to obtain the eventual elimination of taxation? If so, the scheme proposed would immediately reduce the degree and extent of coercion in the system.

Third, the extended taxation would not be associated with reduced income (from the loss of the potential gains from reduced taxation) on the part of taxpayers except for a short period. The specific use made of the surplus revenues under the scheme proposed would in fact result in increased real after-tax incomes available to people for their discretionary use due to the productivity growth already discussed. It is very difficult to see a loss, then, from the temporary continuance of taxation at rates greater than required to fund current functions.

This also provides the answer to another potential objection. The proposed scheme may be argued to involve an unjust intergenerational wealth transfer, since the present generation is taxed so that future generations may go untaxed. But the real situation is quite different since the present generation would gain due to the use made of the revenues. Nor is it clear that they would gain less than future generations. The efficiency of the economy would increase with the elimination of taxation, but the growth of the financial and physical capital pool would slow at that point. What the intergenerational effects would be are not obvious. All that is obvious is that both the present and future generations would gain.

Some libertarians might object that large portions of the annual surpluses would be used to purchase stocks (and bonds) rather than simply deposited, resulting in government ownership and/or control of a great many firms. This scheme could be argued, in other words, to be a back-door form of socialism. In the absence of the power to subsidize, however, it is difficult to see how the character or operations of such firms would be altered. They would still be market institutions subject to competitive discipline, and all of their stockholders would be interested in their efficient operation. Besides, if some legitimate objection to government stock purchases were discovered such purchases could be prohibited by a clause in the legislation creating the system.

Keynesian economists will object to the program set forth here by arguing that the consequence of the surpluses proposed would be an enormous decrease in aggregate demand, severely reducing employment and output. 10 However, in the absence of any alteration in the monetary growth rate, there is no reason to suppose that deficits or surpluses add to or detract from total spending in the slightest. Every dollar government adds to spending in covering a deficit, for example, is simply a dollar lost to private consumption or investment spending on the part of the11 bondholder from whom the government borrowed the money.

In the case of a surplus the option faced by the government is whether to pay off bondholders or deposit the funds. However this decision is made there will be a dollar added to private consumption or investment spending for each dollar of reduced government expenditure.12 Aggregate money expenditure will not change, though this does not mean the economy will not be affected. What the proposed surpluses would do is redirect spending from socialist programs which simply circulate money and discourage production to investments in physical capital and durable goods which increase production.

The possibility of paying bond holders raises the issue of the existing national debt, which has not yet been mentioned. Certainly the legitimate governmental expenditures would have to be defined to include payments on the debt. In 1980 and 1981 federal interest payments were running about 12 percent of receipts. This has risen, but it is still less than 20 percent. Thus it should be possible to make such payments along with expenditure on the other justifiable functions of government and still run a healthy surplus. With the elimination of continued federal borrowing the existing debt would be gradually retired as outstanding bonds matured. It is true, however, that the necessity for debt service increases the length of time required for the federal deposits to raise its interest revenue to the level of its annual outlays.

Perhaps the most serious problem may lie in which economists term the elasticity of demand, in particular, of the capital (or credit) demand curve. Government revenue from its deposits (and investment) base and the market rate of interest, a problem might arise as to the growth of the deposit base caused by the interest rate to decline. If a point were reached at which the demand curve was elastic, that is the percentage decline in the interest rate exceeding the percentage increase in the base, interest revenue would begin to decline.

The question, then, is whether the (net) revenue curve would peak at a level large enough to finance justified annual expenditures. If it did not, upon the elimination of taxes (which should be specified in the initial law to occur either when revenue covers expenditures or when revenue starts falling) some other non-coercive means or obtaining revenue would have to be applied to cover residual expenditures. Examples might include voluntary contributions, lotteries, Federal land sales, or user fees.13

The probability is, however, that the problem would not arise. For one thing, international financial markets are highly integrated, which means that the capital supply curve is elastic for anyone country in the system. As a result, interest rate movements are somewhat restricted. For another, the economic growth stimulated by the lower interest rate 'Would tend to shift both the capital demand and supply curves out. The net effect would almost certainly be an elastic response to revenue from the deposits.

The existence of international capital market integration raises another point. The presence of significant externalities in a market 'Will prevent efficient resource use. 14 It could be argued that such an externality exists and would operate in the case supposed. It is true that the fiscal policy advocated and the consequent fall in interest rates would probably result in significant capital exportation. If so, a good deal of physical capital and productivity growth would therefore occur outside the United States.

If this financial and physical capital transfer went uncompensated, an externality could be said to occur, and domestic financial capital accumulation could be said to be excessive, but a closer look shows it would not. Domestic investments in foreign countries 'Would earn returns, and dollars accumulated in foreign balances 'Would sooner or later be used to purchase domestic goods and services. The international accounts must balance. The capital account deficit would be matched by a current account surplus, just as, currently, our account deficit resulting from federal borrowing is matched by a capital account surplus.15 Clearly no externality is involved.

The least serious objection to the idea proposed here is that it is politically unfeasible. There was a time when a largely market directed, limited government society 'Was thought to be utopian, and its institutionalization 'Was politically unfeasible. Nevertheless the conditions arose for the emergence of such a society, and did so to no small extent as a consequence of education and political struggle by those who conceived the benefits of such institutions. As Mises put it:

Any existing state of social affairs is the product of ideologies previously thought out. Within society new ideologies may emerge and may supersede older ideologies and thus transform the social system. However, society is always the creation of ideologies temporally and logically anterior. Action is always directed by ideas; it realizes what previous thinking has designed .16

III

Some evidence on the economic feasibility of the proposed institutional innovation may be indicated by the experience of Hong Kong. Hong Kong is one of the few remaining British crown colonies, and has never had an indigenous democratic government. As such it has faced relatively little pressure for imposition of welfare state practices. In fact its administrators have, in contradistinction, followed a highly laissez-faire policy. This policy has resulted in very rapid output and real income growth, despite extremely limited physical resources and a population density which is not only large, but increasing, due to refugee immigration as well as internal growth.17

There are several factors behind this growing prosperity. The government has largely restricted itself to maintaining order, and tax rates have been kept very low. The presence of a large amount of cheap labor, kept cheap by inexpensive food imports -- attributable to a policy of complete free trade -- and by a near absence of labor legislation (until recently), has meant a high rate of return to entrepreneurs. This high rate of return, in combination with the political conditions in communist China, has resulted in expatriate Chinese throughout Asia investing large amounts of capital in Hong Kong. 18

A less noticed factor in Hong Kong's growth is that, despite its low tax rates, the government has systematically run budget surpluses for several decades. 19 Infrequent deficits have occurred but have been easy to cover from the accumulated surplus revenue.20 It has been recently reported that the annual interest on these cumulative deposits is sufficient to cover nearly 40 percent of annual government expenditures. What is more, this proportion could clearly be increased rather rapidly, since, despite its laissez-faire character, the Hong Kong government is engaged in a number of semi-socialistic enterprises and interventionist pursuits which could be easily eliminated from the budget.2l

Economic phenomena are intrinsically complex, and with so many factors favoring economic growth in Hong Kong, it would be extremely difficult to disentangle the effect of the budget surpluses from those of the capital importation, low tax rates, paucity of regulation, free trade, etc., even were the required data available. 22 Statistical study of the issue therefore remains a matter for future research, though a priori the effect is positive, and there certainly seems little evidence of the contractionary effect postulated by the Keynesians.

Some will object, as they already have, that the historical and institutional situation of Hong Kong is unique and not applicable elsewhere. 23 But the very fact that a nation has been able to practice such policies, with such undeniably beneficial results, casts doubt on the nation that they could not be practiced elsewhere, particularly in the United States, which has history of limited government and a philosophy of laissez-faire.24 If Hong Kong can restrict government activities and run budget surpluses until the interest earned is capable of covering a major portion of its annual expenditures, then why could not this policy be extended to cover 100 percent of such expenditures? And if Hong Kong could do this, why not the home of the brave and the land of the free?

NOTES AND REFERENCES

1) See Ayn Rand, "Appendix: The Nature of Government," in Capitalism, the Unknown Ideal (New York: Signet Books, 1967): 330-331

2) The intellectual leader of the anarcapitalist wing of the libertarian movement is Murray Rothbard. See his For a New Liberty (New York: Macmillan, 1973), and his Power and Market Government and the Economy (Menlo Park, California: Institute for Humane studies, 1970). Leading minarchist libertarians include the late Ayn Rand and John Hospers. See his Libertarianism (Los Angeles: Nash Publishing Co., 1971): chapter 1.

3) This is exactly the way the government of Hong Kong operates. See below.

4) It is quite possible for government to spend money in ways which increase the nation's capital stock, as, for example, when it builds dams and highways. But particularly given the shift in the composition of the budget towards income transfer programs in the last two decades, it is not doing so on net.

5) A critic of an early draft of this paper made a valid point here by pointing out that it is not enough to insure efficiency that the maximum of funds available is fixed. There also has to be a fear that the minimum is not fixed. The critic then denied that endowed chairs in the academy were under tremendous pressure to operate efficiently. But surely: they are under more pressure, and do operate more efficiently that does government, to which neither the maximum nor the minimum is fixed under the current structure.

6) Subject to the limits of the Laffer Curve, of course.

7) This is admitted even by liberal economists. See William Baumol and Alan Blinder, Economics: Principles and Policy (New York: Harcourt Brace Javanovich, 1982): 561-568.

8) This is not speculation. Both of these objections and the "intergenerational transfer" objection discussed below were explicitly made by the critic mentioned in note 5 above.

9) We may wish this were not so, but it clearly is, and will continue to be the case until the public is convinced that some practical, non-coercive, alternative means of governmental finance is available.

10) The reasoning here is that taxation reduces disposable income and therefore reduces consumer spending, so this reduction must be offset by government spending if a contraction in total spending is to be avoided. See Paul Samuelson, Economics (l0th edition, New York: McGraw-Hill, 1976): 288. For the fallacy in this reasoning, see below.

11) See Norman B. Ture, "Supply Side Analysis and Public Policy," in David G. Raboy, ed., Essays in Supply Side Economics (Washington D.C.: The Institute for Research on the Economics of Taxation, 1982): 13-16.

12) The same reasoning applies whether the surplus results from a reduction in government spending, as supposed here, or from an increase in taxation. In the latter case, however, the increased private consumption and investment spending

attributable to the deposits and debt payments would offset reduced private consumption and investment due to the increased taxation.

13) As an example in the latter category, the government might be allowed to operate the Interstate highway system on a toll basis, sharing the net revenue with the states in a proportion determined by their original contributions to the construction costs. Competition from state roads would keep the tolls low, and users would pay the full cost of their driving, as they should.

14) On the nature of the externality problem, see Steven N. S. Cheung, The Myth of Social Cost (London: Institute of Economic Affairs, 19m 2I-68.

I5) Martin Feldstein, William Niskanen and William Poole, "Annual Report of the Council of Economic Advisors," Economic Report of the President (Washington D.C.: U.S. Government Printing office: 1984): 42-57.

16) Ludwig von Mises, Human Action (3rd revised ed., Chicago: Henry Regnery, 1963): 188.

17) What is more, this rapid growth seems to have been associated with increasing, not decreasing, equality of incomes. See Steven C. Chow and Gustav F. Papanek, "Laissez-Faire, Growth and Equity --Hong Kong," Economic Journal 91 (June 1981): passim.

18) Alvin Rabushka has written extensively on the economics, history, and economic history of Hong Kong. See his The Changing Face of Hong Kong (Washington D.C.: The American Enterprise Institute, 1973), and Hong Kong : A Study in Economic Freedom (Chicago: University of Chicago Press: l979).

19) The government does not claim this is deliberate, but the pattern is clearly systematic. See The Changing Face of Hong Kong: 54-58, and Hong Kong: A Study in Economic Freedom: 51-55.

20) A public debt does exist, but it is extremely small. See The Changing Face of Hong Kong, 55.

21) See above: 58-79.

22) In accord with its laissez-faire policy, the government of Hong Kong did not even collect G.N.P. statistics until the mid-1970s. This led to much criticism from social scientists, of course. See The Changing Face of Hong Kong: 21-29. However, such information was never entirely missing. Some statistical data can be found in the Hong Kong Annual Report, and the Hong Kong Monthly Digest of Statistics,

23) Rabuska flnd that the historical and institutional situation of Hong Kong is not unique. See Hong Kong: A Study in Economic Freedom: Chapter lV.

27) Indeed, the United States has actually had extensive historical experience with budget surpluses. For over 150 years the U.S. basically followed a balanced budget policy. Wartime finances always resulted in heavy borrowing, but following a war

persistent surpluses would be run until the debt was either eliminated or greatly reduced. On this history see Richard Wagner, Robert Tollison et al., Balanced Budgets, Fiscal Responsibility and the Constitution (Washington D.C.: the Cato Institute, 1982): It is also worth noting that at least two of these periods of extended post-war surpluses, those following the Civil War and World War ll, were notable periods of rapid growth and prosperity.